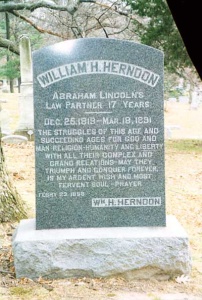

Billy Herndon was the son of Archer Gray Herndon (a member of "the Long Nine" a group of men who got the state capitol of Illinois moved to Springfield - so named because they were all over 6' tall). Billy was Lincoln's 3rd & last law partner. After Lincoln's death, he devoted his life to researching Lincoln's life.

Lincoln had told him he never read biographies because they were all lies. (At that time, bios were written in romantic style and rarely said anything negative about anyone.)

Herndon was determined to write an accurate account of Lincoln's life, believing he would want it that way. Nearly every book written about Lincoln used some of Herndon's research. He was much hated at the time for his writings. After many years of giving his research to other writers, he finally agreed to co-author the book "Herndon's Lincoln," which is in libraries and available for sale today.

Author of Herndon's Lincoln: the true story of a great life ... The history and personal recollections of Abraham Lincoln, by William H. Herndon, Jesse William Weik, et al, 1889.

David Herbert Donald wrote a biography of William H. Herndon called "Lincoln's Herndon: A Biography," published in 1948.

Herndon, Kansas

Herndon Kansas's history began in May 1876 when Lorenz and Sophia Demmer came from Smith County, Kansas to stake their homestead claim in SE 4 of Sec. 3-2-31. Their first residence was a cave in the banks of Ash Creek at the east edge of what would become the town of Herndon. In the spring of 1877 the first of many Austrian-Hungarian immigrants, Mathias and Teckla Hafner, homesteaded a mile west of town.

The autumn of 1879 saw merchant I. N. George haul in a wagon train of merchandise and supplies. He put up a building and opened the first general store in Herndon and in Rawlins County. A year later Mr. George became postmaster of the town then called "Pesth. He got the town's name changed to Herndon to honor Billy Herndon, who was Abraham Lincoln's law partner.

==================================

Excerpt from "Lincoln and Whitman," by Daniel Mark Epstein, 2004

Springfield, 1857

Abraham Lincoln's law partner William "Billy" Herndon, thirty-nine, loved the birds and wildflowers of the prairie, pretty women, and corn liquor. He also had an immoderate passion for new books, and for the transcendental philosophizing of pastor Theodore Parker and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. By his own accounting he had spent four thousand dollars on his collection of poetry, philosophy, and belles lettres-a fortune in those days, when a good wood-frame house in Springfield, Illinois, cost half as much. Journalist George Alfred Townsend called Herndon's library the finest in the West.

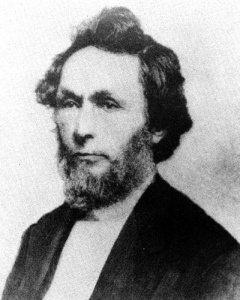

Herndon's narrow, earnest-looking face was fringed with whiskers in the Scots manner, and his eyes were close-set, intense. His favorite philosopher-poet was Emerson. Herndon so admired the Sage of Concord that he purchased Emerson's books by the carton and gave them away to friends and strangers with the zeal of an evangelist. A backwoods philosopher, Herndon even solicited Emerson's endorsement for his tract "Some Hints on the Mind," in which he claimed to have discovered the mind's fundamental principle, "if not its law."

So when Emerson espoused a new book of poetry, calling it "the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed," Herndon wasted no time in locating a copy, which could be found on the shelves of R. Blanchard's, Booksellers, in Chicago, where he frequently traveled on business.

Having held the olive-green book, its cover blind-stamped with leaves and berries; having regarded with a twinge of envy the salutation "I Greet You at the / Beginning of A / Great Career / R W Emerson," gold-stamped on the spine, the bibliophile-lawyer plunked down his golden dollar for the second edition of Whitman's Leaves of Grass. And knowing the storm the book had caused in more sophisticated circles, Herndon brought the brickbat-shaped volume to the office he shared with Lincoln and set it in clear view on the table, where anyone might pick up the book and thumb through it. Leaves of Grass was exactly the length of a man's hand. He laid it down on the baize-covered table with the complacence of an anarchist waiting for a bomb to explode.

The Lincoln-Herndon law office was on the second floor of a brick building on the west side of Springfield's main square, across from the courthouse. Visitors mounted a flight of stairs and passed down a dark hallway to a medium-sized room in the rear of the building. The upper half of the door had a pane of beveled glass, with a curtain hanging from a wire, on brass rings. Lincoln would unlock the door, open it, and draw the curtain as he closed the door behind him. Two dusty windows overlooked the alley.

Herndon's biographer David Donald describes the office as "a center of political activity, of gossip and friendly banter, and of such remote problems as the merits of Walt Whitman's poetry."

The office was untidy and cobwebbed. Once, after Lincoln had come home from Congress with the customary dole of seeds to distribute to farmers, John Littlefield, a law student, discovered while sweeping that some of the stray wheat seeds had sprouted in the cracks between the floorboards. A long pine table that divided the room, and met with a shorter table to make a T, was scored by the jackknives of absent-minded clerks and clients. In one corner stood a secretary desk, its many pigeonholes and drawers stuffed with letters and memoranda, its besieged surface sustaining a spattered earthenware inkwell and a few gold pens. Bookcases rose between the tall windows. A spidery black stain blotted one wall, at the height of a man's head, where an ink bottle had exploded-the memento, according to Lincoln, of a disagreement between law students over a point of jurisprudence that would not yield to cold logic.

Papers were strewn everywhere, as if by a prairie wind: on the table, on the floor, on the five scattered cane-bottomed chairs and the ragged sofa where the senior partner of the firm liked to stretch out his full length, his head on the arm of the sofa. His legs were too long to fit the settee, so Lincoln would rest his feet on the raveling cane seat of a chair. There he reclined every morning, after arriving at nine, clean-shaven. And he would read, aloud. He read newspapers and books, always aloud, much to the annoyance of his partner, who found the high, tuneful voice, with its chuckling interludes and asides, a distraction from the warrants and writs and invoices. Herndon once asked Lincoln why he had to read aloud, and the forty-eight-year-old ex-Congressman explained: "Two senses catch the idea: first I see what I read; second I hear it, and therefore I can remember it better." Lincoln-not boasting-said that his mind was like steel: the gray matter was difficult to scratch, but once engraved on it, information was nearly impossible to efface. According to Herndon, Lincoln did not read many books, but whatever he did read he absorbed completely.

The law students got to Whitman first. Perhaps they had read about Leaves of Grass in Putnam's Monthly Magazine, where the eminent Charles Eliot Norton had announced that words "banished from polite society are here employed without reserve" and called the book a curious mixture of "Yankee Transcendentalism and New York rowdyism"; or they might have caught notice of it in the New York Criterion, where the dyspeptic Rufus Griswold referred to it as "this gathering of muck." In America's most influential literary journal, the North American Review, Edward Everett Hale rhapsodized about Leaves of Grass. And in May 1856 no less an authority than Fanny Fern-the highest-paid columnist in the country-referred to Whitman in the New York Ledger as "this glorious Native American." The book was widely praised and condemned, much discussed, if not much purchased or read.

According to Henry Bascom Rankin, who was a student in the Lincoln-Herndon office in 1857, "discussions hot and extreme sprung up between office students and Mr. Herndon concerning its poetic merit." A few verses:

I mind how we lay in June, such a transparent summer morning,

You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my bare-stript heart . . .

I turn the bridegroom out of bed and stay with the bride myself,

I tighten her all night to my thighs and lips.

Poetry indeed! These long, racy, unrhymed verses did not look like any poetry the provincial law students had ever seen, no matter what Emerson or the bluestocking Fanny Fern wrote.

The talk of Whitman that animated the law office during the unseasonably warm spring of 1857 relieved the furious, anguished discussion of the Supreme Court's recent decision about Dred Scott, which aroused Lincoln from a spell of political torpor. Yet even Scott's fate led them back to Leaves of Grass:

I am the hounded slave, I wince at the bite of the dogs,

Hell and despair are upon me, crack and again crack the marksmen,

I clutch the rails of the fence, my gore dribs, thinned with the ooze of my skin . . .

The argument over Whitman did not differ much in Springfield from the dispute in Boston and New York. Was this poetry? Then there arose the livelier controversy over the book's brazen immodesty. Was Leaves of Grass indecent? Many of the verses sounded shameless, unfit for mixed company. Take for example the anonymous woman watching twenty-eight young men bathing by the shore, who comes "Dancing and laughing along the beach" to caress their naked bellies:

They do not know who puffs and declines with pendant and bending arch,

They do not think whom they souse with spray.

Was this Walt Whitman actually depicting a sexual act outlawed everywhere but in the debaters' dreams? It was shocking, pornographic. The men wondered whether such a book should be allowed on library shelves, or in homes where women and children might casually be seduced by it. Who was responsible for the corruption of morals: the author, the printer, the Chicago bookseller, or buyers of Leaves of Grass like Billy Herndon?

The students wrangled, and read the poems aloud, with Herndon sometimes acting as Whitman's advocate, other times as an impartial referee. Visitors dropping by, such as Dr. Newton Bateman, superintendent of schools, would join in the discussion provoked by lines such as:

A woman waits for me-she contains all, nothing is lacking,

Yet all were lacking if sex were lacking, or if the moisture of the right man were lacking.

Lincoln worked quietly at his desk, raking his coarse hair with his long fingers, or he came and went, apparently oblivious to the disturbance the new book was causing in the workplace. Having lost a year to politics, stumping for the Republican John Frémont during the presidential campaign of 1856, advocating "free soil, free labor and free men," he had a lot of catching up to do in his neglected law practice. He was also having a spell of depression, "the hypochondria," as it was called in those days. This mood afflicted him periodically, often between periods of intense business or creative work. So he turned his back on the students, and Herndon and Dr. Bateman, as they challenged one another's taste in literature and questioned one another's morals, reading passages of Leaves of Grass and attacking or defending Whitman as the spirit, or the letter, moved them. The poet was utterly uninhibited, whether he was describing himself, or addressing the President:

Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos,

Disorderly, fleshy, sensual, eating, drinking, breeding,

No sentimentalist, no stander above men and women, or apart from

them-no more modest than immodest

. . .

I speak the pass-word primeval, I give the sign of democracy,

By God! I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart

of on the same terms.

Have you outstript the rest? Are you the President?

It is a trifle-they will more than arrive there every one, and still pass on.

One day, after the debaters had departed, a few clerks, including Henry Rankin, remained, copying documents. Lincoln rose from his desk. This was always a sight because sitting down Lincoln appeared to be of average height, but his limbs were so disproportionately long that when he unfolded and stretched them it was as if a giant had sprung up out of a common man.

"Quite a surprise occurred," Rankin recalled, in a memoir written years later. Lincoln picked up the book of poems that had been disturbing the peace and began to read, as he rarely did, in devoted silence, for more than half an hour by the Regulator clock. When the pressure of perusing the poetry silently became more than Lincoln could endure, he thumbed back to the first pages of Leaves of Grass and began reading aloud, in that tenderly expressive voice with the Kentucky accent and continual undercurrent of whimsical humor.

I celebrate myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease, observing a spear of summer grass.

The light of afternoon streamed through the office windows, gilding the dust motes.

Houses and rooms are full of perfumes-the shelves are crowded with perfumes,

I breathe the fragrance myself, and know it and like it,

The distillation would intoxicate me also, but I shall not let it.

The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has no taste of the distillation, it is odorless,

It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood, and become undisguised and naked,

I am mad for it to be in contact with me.

The smoke of my own breath,

Echos, ripples, buzzed whispers, love-root, silk-thread, crotch, vine

My respiration and inspiration, the beating of my heart . . .

"His rendering," Rankin remembered, "revealed a charm of new life in Whitman's versification." Here and there Lincoln found a verse too coarse, a line or phrase he felt the poet might have avoided. But on the whole he "commended the new poet's verses for their virility, freshness, unconventional sentiments, and unique forms of expression."

Lincoln put the book back down on the office table, desiring Herndon to leave Whitman there where he might not get lost in the tide of books, newspapers, and documents. "Time and again, when Lincoln came in, or was leaving, he would pick it up, as if to glance at it for only a moment, but instead he would often settle down in a chair and never stop reading aloud such verses or pages as he fancied."

Once Lincoln made the mistake of taking Leaves of Grass home. The next morning he brought the book back, grimly remarking that he "had barely saved it from being purified in fire by the women." This anecdote goes a long way toward explaining the politician's lifelong reticence about the poet and his book. Of course, by "the women" he meant his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, who controlled nearly everything that went on inside the big, two-story house at the corner of Eighth and Jackson where they lived with their three boys.

It is uncertain what verses or pages Lincoln fancied. The feuds among Lincoln's early biographers, struggling over the soul of the martyred President, have few parallels in American letters. In 1928 a rival biographer, Reverend William E. Barton, in a popular book that took pains to disassociate Lincoln from Whitman, challenged Rankin's memory. As early as 1932, however, the scholar Charles Glicksberg, in Whitman and the Civil War, declared that Barton's book was "marked throughout by a hostile spirit toward Whitman" and discredited Barton's premise that Lincoln was unaware of Whitman's existence. Modern scholars, such as Whitman biographers Gay Wilson Allen and Jerome Loving, and David Herbert Donald, who wrote books on both Herndon and Lincoln, likewise have accepted Rankin's story in spite of Reverend Barton.

One of the points that authenticate Rankin's account is his dating of Lincoln's encounter with Leaves of Grass. Only in that year, two years after the first publication of Whitman's poems in 1855, would the ex-Congressman and future President Lincoln have had the freedom and inclination to study such a literary curiosity. Only in 1857 could the reading of Whitman have produced such an impact on his oratory.

Billy Herndon, who knew Lincoln better perhaps than any man in Lincoln's day, said he was the rare man without vices, but with a flagrant disregard for propriety, "the appropriateness of things." He was so heedless of his appearance that he forgot to comb his coarse black hair. He cared so little about clothing that sometimes he wouldn't wear this piece or that. After all, he was raised on a farm in Kentucky, barefoot. "He never could see the harm in wearing a sack-coat instead of a swallowtail to an evening party, nor could he realize the offense of telling a vulgar yarn if a preacher happened to be present."

==================================

"William H. Herndon and Mary Todd Lincoln," by Douglas L Wilson:

http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jala/22.2/wilson.html

William Henry Herndon

William Henry Herndon

- b.1649 in Marden, Maidstore, Kent, England d.1722 in Hampton Parrish, York County, Virginia

- b.1649 in Marden, Maidstore, Kent, England d.1722 in Hampton Parrish, York County, Virginia

- b.Mar 1678 in St. Stephens Parish, New Kent County, Virginia d.09 Mar 1758 in Caroline County, Virginia

- b.Mar 1678 in St. Stephens Parish, New Kent County, Virginia d.09 Mar 1758 in Caroline County, Virginia

- b.~ 1654 in Hampton, Elizabeth City, Virginia d.1729 in Caroline County, Virginia

- b.~ 1654 in Hampton, Elizabeth City, Virginia d.1729 in Caroline County, Virginia

- b.1706 in King and Queen County, Virginia d.1783 in King and Queen County, Virginia

- b.1706 in King and Queen County, Virginia d.1783 in King and Queen County, Virginia

- b.23 May 1674 in Newport, Pagnell, Buckinghamshire, England d.1727 in Caroline County, Virginia

- b.23 May 1674 in Newport, Pagnell, Buckinghamshire, England d.1727 in Caroline County, Virginia

<Unknown>

<Unknown>

- b.26 Jan 1745 in Orange County, Virginia d.26 Oct 1828 in Green County, Kentucky

- b.26 Jan 1745 in Orange County, Virginia d.26 Oct 1828 in Green County, Kentucky

- b. in St. Martin in the Fields, Westminister, London, England d.22 Jul 1726 in Williamsburg, Virginia

- b. in St. Martin in the Fields, Westminister, London, England d.22 Jul 1726 in Williamsburg, Virginia

- b.1712 in King and Queen County, Virginia d.1777 in Orange County, Virginia

- b.1712 in King and Queen County, Virginia d.1777 in Orange County, Virginia

- b.13 Feb 1795 in Madison County, Virginia d.03 Jan 1867 in Springfield, Illinois

- b.13 Feb 1795 in Madison County, Virginia d.03 Jan 1867 in Springfield, Illinois

- d.19 Aug 1875 in Springfield, Illinois

- d.19 Aug 1875 in Springfield, Illinois